A blog series recounting our adventures in the quest to port the BEAM JIT to the ARM32-bit architecture.

This work is made possible thanks to funding from the Erlang Ecosystem Foundation and the ongoing support of its Embedded Working Group.

First Printed Line From the ARM32 JIT

On February 13, 2026 we managed to execute the erlang:display_string/1 BIF and print characters on the shell. The string is: "Everything is fine!\n"

qemu-arm -L /usr/arm-linux-gnueabihf ./otp/RELEASE/erts-15.0/bin/beam.smp -v -A 0 -S 1:1 -SDcpu 1:1 -SDio 1 -JDdump true -JMsingle true -- -root /home/vagrant/arm32-jit/otp/RELEASE -progname erl -home /home/vagrant

Verbose level: SYSTEM

Allocated 32768 atom space

Emitting function hello:start/2

Emitting function hello:hello/1

Emitting function hello:module_info/0

Emitting function hello:module_info/1

Emitting function erlang:adler32/1

Emitting function erlang:adler32/2

...

Emitting function erlang:module_info/0

Emitting function erlang:module_info/1

Emitting function erlang:'-inlined-error_with_inherited_info/3-'/3

Everything is fine!

qemu: uncaught target signal 11 (Segmentation fault) - core dumpedThe other things you see in the truncated log are debug prints to check which functions we have emitted, and the final segmentation fault. More about that later.

We are using a minimal version of hello.erl, this time with two major additions:

- Using the

erlangmodule to accessdisplay_string; this requires loading all oferlang.beam, which is a huge module. - Embedding the call in a local Erlang function

start(_BootMod, BootArgs) ->

hello(BootArgs),

halt(42, [{flush, false}]).

hello(_BootArgs) ->

erlang:display_string("Everything is fine!\n"). % 🤡Looking at the assembly

We can see that since the previous post, things have changed a bit. We are now using call to execute the hello function. Inside hello, we use call_ext_only, while for halt/2 we now use call_ext_last.

{module, hello}. %% version = 0

{exports, [{module_info,0},{module_info,1},{start,2}]}.

{attributes, []}.

{labels, 9}.

{function, start, 2, 2}.

{label,1}.

{line,[{location,"otp/erts/preloaded/src/hello.erl",74}]}.

{func_info,{atom,hello},{atom,start},2}.

{label,2}.

{allocate,0,2}.

{move,{x,1},{x,0}}.

{line,[{location,"otp/erts/preloaded/src/hello.erl",75}]}.

{call,1,{f,4}}. % hello/1

{move,{literal,[{flush,false}]},{x,1}}.

{move,{integer,42},{x,0}}.

{line,[{location,"otp/erts/preloaded/src/hello.erl",76}]}.

{call_ext_last,2,{extfunc,erlang,halt,2},0}.

{function, hello, 1, 4}.

{label,3}.

{line,[{location,"otp/erts/preloaded/src/hello.erl",79}]}.

{func_info,{atom,hello},{atom,hello},1}.

{label,4}.

{move,{literal,"Everything is fine!\n"},{x,0}}.

{line,[{location,"otp/erts/preloaded/src/hello.erl",87}]}.

{call_ext_only,1,{extfunc,erlang,display_string,1}}.

%% Module info sections...This is the erlc compiler doing its business. call_ext_only is enough for a simple external function call done as a tail call. Nothing else was allocated in hello, so that is enough.

In the start function, we instead have a new allocate instruction, so call_ext_last is probably linked to that.

Now let's have a look at the JITted assembler for the new interesting part.

...

# ....

# hello:start/2

blx L10

.byte 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00

.byte 0x0B, 0x4F, 0x00, 0x00, 0x0B, 0xA4, 0x00, 0x00, 0x02, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00

# aligned_label_Lt

start/2:

# i_breakpoint_trampoline

str lr, [r7, -4]!

b L11

bl L13

L11:

# i_test_yield

adr r2, start/2

subs r9, r9, 1

b.le L15

# allocate_tt

# i_move_sd

ldr r12, [r4, 68]

str r12, [r4, 64]

# line_I

# i_call_f <---- Our new local f call

sub r12, r7, 4

cmp r10, r12

b.ls L17

udf 48879

L17:

bl @label_4-0 # <--- label_4 is where hello() is

# ..................................................................

# call to halt

# ..................................................................

# i_func_info_IaaI

# hello:hello/1

# ...

label_4:

# i_breakpoint_trampoline

str lr, [r7, -4]!

b L29

bl L13

L29:

# i_test_yield

adr r2, label_4

subs r9, r9, 1

b.le L15

# i_move_sd <---- Loading our string in X[0]

ldr r12, [L30]

str r12, [r4, 64]

# i_call_ext_only_e

ldr r0, [L31]

ldr lr, [r7], 4

ldr r12, [r0, r5 lsl 3]

bx r12 # <--- branch towards erlang:display_string/1 BIFThere is a lot of hidden complexity in calling a BIF. To give you an idea of what happens after branching, I put a breakpoint in the display_string_2 function.

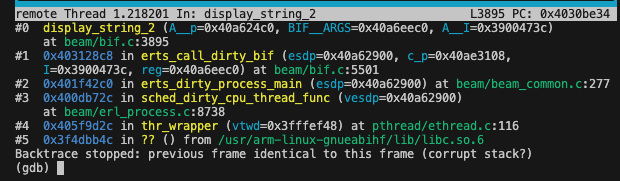

In this screenshot from GDB it seems like we are ending up in a separate thread, maybe the dirty IO scheduler...

At the time of writing, we are not completely sure where we are crashing after the execution of display_string.

From what I traced so far in GDB, the call triggers a context switch and a garbage collect check. Then a new iteration in the process_main loop happens.

Later we reach the section of an emitter which we still have not implemented. We know how to proceed, but we also noticed that we are occasionally experiencing a corruption of the stack. More about that later...

Workflow

Following the instructions through JITted assembly is tough. I am mostly working with GDB using layout asm. This layout allows me to view the ARM32 assembly live during execution. To proceed instruction after instruction, I use the stepi command. This mode is ideal to review the JITted code sections and understand in full detail what is happening.

The hardest part is knowing where we are. As we are emitting new code every run, I cannot set breakpoints beforehand. Sure, subsequent executions will place instructions at the same addresses, but this will not be true as soon as I add or remove code. What I do to reach a precise point is a mix of the following:

- I break at the nearest C runtime invocation I know of. This could be, for example:

- erts_schedule

- apply

- display_string_2

- beam_jit_call_nif

From there you can proceed with patience, keep track of where you are, and wait to reach the part of code that leads to failure.

- Recognize assembler sections.

Since I have ported a few assembly emitters from ARM64 to ARM32, it is easy to recognize the same instruction sequences in GDB. These sequences can become familiar and help to recognize where I am. This is crucial as I need to know at all times which emitter is directly linked to the code I am debugging, so that I know which C function I need to edit.

- Emit NYI everywhere

In OTP there is this magical emitter: emit_nyi that we can paste EVERYWHERE. This little guy puts a string into ARG1 and calls i_emit_nyi. This runtime function will print the string and exit the VM.

This allows us to:

- Port every ARM64 emitter function in ARM32 with empty body

- Put

emit_nyi("the_name_of_this_emitter")everywhere - Profit (?!)

A bit of context

The emitters will be called by the BEAM loader. Keep in mind that the emitters are not a direct representation of BEAM instructions. The erlc compiler generates high-level (generic) BEAM instructions; the loader transforms them into specific BEAM instructions. This is done by generated C code. The logic is encoded in .tab files, compiled to C by the beam_makeop Perl script. This, quite frankly, is a huge rabbit hole we still have not dug into. For now we are just using the same translation as ARM64 and porting the emitters; then we will see how far we get.

The advantage of using emit_nyi is that we always know what the next JIT code section to implement is. We do not need to know how instructions are translated or what should be called next. Since we are borrowing from ARM64, we let the loader choose the emitters, and during execution we discover which one is the next to write.

This is handy of course, given that we are able to actually load...

Loading huge modules

To print "Everything is fine!\n" we need the erlang module to access display_string/1. For halt/2 we did not need it, as that BIF is special. The compiler allows calling it in any module. Until the last post we were loading just the tiny hello.erl, but now we need to load the whole erlang.erl:

- ~12000 lines of code

- ~35000 lines of assembler

InvalidDisplacement: ldr r3, [L2884]

This asmjit error greeted me when I first attempted to load the module. The problem is that label L2884 is too far away, and the address that should be encoded here is too big for ARM32, and therefore, invalid.

To debug, I initially placed an erts_fprintf in beam/jit/asm_load.c to print the module, name, and arity of every function that was going to be emitted.

It looked like:

...

Emitting function erlang:receive_allocator/3

Emitting function erlang:gather_gc_info_result/1

Emitting function erlang:gc_info/3

Emitting function erlang:'=='/2

Emitting function erlang:'=:='/2

Emitting function erlang:'/='/2

...The function where it stopped was not always the same, so the problem was probably not tied to a specific instruction used in the function. Remember that we are emitting NYI everywhere, so in theory we should be able to load without issues as everything is just calls to NYI anyway.

The good thing was that the label — but more importantly, the instruction — was always the same: ldr r3, [label]. By printing the call stack with GDB (bt command) I found which line was giving problems.

This line, in beam_asm.hpp

a.ldr(tmp, embed_constant(arg, disp4KB));We are loading an embedded constant with ~4KB displacement specified by an enum. embed_constant is that classic C function that does many more things than what the name says. In a few words, it takes care of giving you the address of the constant, abstracting the hassle of managing it.

But to debug this issue we need to actually understand how constants are embedded...

To break it down briefly:

If the constant is new:

New means either truly new, or previously used but now too far away to reference.

- Stores a new constant value in a data structure for later,

- assigning a unique label ID (like L2884 in our case)

- stores the actual value

- stores the maximum offset this label can be embedded.

- Stores it in the

pending_constantslist. This is done because the JIT needs to remember that this constant must be embedded at some point.

If the constant is not new and is in range (not used too far away), we can recycle it. When we recycle it, we need to pay attention to where we are. We could be in two situations:

The label was used but is still unbound, which means its position in the assembly code has not been decided yet. We just need to make sure we are not too far away from the first usage, stored when the constant was created.

The label was used and is already bound to a place. We do not care when it was first used. We need to check our distance from the anchor, which is the reference to the place where the label will be embedded.

Truth be told, constants and labels are resolved after all instructions are listed, in a second pass. So for now, the logic is only working with references.

Inspecting the AsmJIT log

I inserted debug prints in embed_constant using the comment() utility, which prints comments in the AsmJIT dump. This lets me place information near the instruction I want to debug. Now that we know how constants are handled, a simple grep L2884 inside erlang.asm will show us the aftermath of the crash:

First occurrence is at line 24402

L2883:

ldr r3, [L2884] # <---

movw r1, 38612

movt r1, 16431

adr r2, L2883The label is used 5 more times and at some point we see it getting placed into a stub around line 25276.

# i_flush_stubs

# Begin stub section

b L2939

L2882:

.xword 0x000000007FFFFFFF

L2884: # <---

.xword 0x000000007FFFFFFF

L2890:

.xword 0x000000007FFFFFFF

# End stub sectionIn the JIT there is a function that is used to flush pending stubs. These flushes are minimized to optimally use the displacement capabilities of instructions like LDR, STR, BX, BL, etc.

The important thing is not to flush too late; that is why new constants are added to the pending_constants list, waiting to be bound in a stub section. For example, the BeamModuleAssembler calls check_pending_stubs(), each time before emitting a specific BEAM operation.

Given that we survived binding the constant and only exploded much later, I only debugged the offsets used in the if case in which the label is present, in range, and bound.

Here I am posting the 2 last usage of L2884, the last one triggers a crash, which means embed_constant made a wrong decision and instead of creating a new constant it kept using L2884.

disp: 4092 is the displacement I set for enum disp4KB and is used as the maximum offset distance. The rest of the comments are self-explanatory.

# reusing bound constant at offset: 64804

# current offset: 68468

# disp: 4092

ldr r3, [L2884] # <--- This is legal

movw r1, 38612

movt r1, 16431

adr r2, L3016

# .... few hundred lines later....

# reusing bound constant at offset: 64804

# current offset: 68892

# disp: 4092

# InvalidDisplacement: ldr r3, [L2884] <- This is not legal :(If we do few calculations we can guess the value that would be fed into LDR:

68468 - 64804 = 3664 =< 409268892 - 64804 = 4088 =< 4092

Both look good; the second is near the 4KB limit imposed by ARM32. This is because on ARM we only have 12 bits available to encode an address for LDR.

12bits -> 2^12 -> 4096 -> 4 Kibibytes

In the ARM32 JIT I had naively set the 4KB displacement as:

enum Displacement : size_t {

// ....

disp4KB = (4 << 10) - sizeof(Uint32),

// ....

};I removed 4 bytes to be safe, as the ARM64 version does, but apparently 4088 is already too much for the spec. Why? Well... by digging a bit I discovered that on ARM32 the displacement you put into LDR needs to be measured not from the address of the current instruction, but from 8 bytes AHEAD — in other terms, PC+8. This means that our math is wrong. We are using this displacement to go back in the code sequence, so the PC+8 constraint works against us and requires us to stop 8 bytes before what I initially accounted for.

The number that AsmJIT is encoding is not 4088 but 4088 + 8 = 4096, and 4096 is actually not legal as the maximum you can encode with 12 bits is 4095.

To fix this bug and successfully load the erlang module, all that is needed is to fix this enum:

enum Displacement : size_t {

// ....

disp4KB = (4 << 10) - 1 - 2 * sizeof(Uint32),

// ....

};And this is the end of the function list of erlang.erl

🥳🥳🥳🥳

...

Emitting function erlang:and/2

Emitting function erlang:or/2

Emitting function erlang:xor/2

Emitting function erlang:not/1

Emitting function erlang:'!'/2

Emitting function erlang:ensure_tracer_module_loaded/2

Emitting function erlang:module_info/0

Emitting function erlang:module_info/1

Emitting function erlang:'-inlined-error_with_inherited_info/3-'/3Yep, even ! is a function 😉

Reaching the first print to stdout

Now, going back to running the JITted code, we can leverage emit_nyi to quickly implement the next emitter, adapting the ARM64 implementation to our ARM32 style and register conventions.

The objective is to reach display_string_2 in beam/bif.c which will print our string.

Guided by the NYI printouts we just needed to implement the following emitter:

- emit_i_call_only: to call

hello - emit_catch

- bif return checks

After these steps, the Everything is fine! string appears. Looks like we are already returning from the BIF. Probably, these instructions happening after the BIF return have given enough time to the IO thread to print to stdout before the program crashes.

Next are other instructions that follow...

- emit_dispatch_bif

- emit_call_bif_shared

- emit_bif_nif_epilogue

- emit_i_breakpoint_trampoline_shared

- emit_call_nif_shared

- ... TODO:

emit_i_test_yield_shared

This is all still WIP, and the next objective is to reach halt and exit without errors, but we’re probably still missing a few emitters and quite a bit of debugging.

Stack corruption? Heisenbug?

The main obstacle right now is to avoid stack corruption when calling runtime functions. We are starting to notice this issue:

Emitting function erlang:'-inlined-error_with_inherited_info/3-'/3

Everything is fine!

NYI: qemu: uncaught target signal 11 (Segmentation fault) - core dumped

./run_clean.sh: line 7: 29488 Segmentation fault (core dumped) qemu-arm -L /usr/arm-linux-gnueabihf ./otp/RELEASE/erts-15.0/bin/beam.smp -v -A 0 -S 1:1 -SDcpu 1:1 -SDio 1 -JDdump true -JMsingle true -- -root /home/vagrant/arm32-jit/otp/RELEASE -progname erl -home /home/vagrantYou see that after successfully printing to stdout we crash while printing "NYI: {name_of_emitter}"

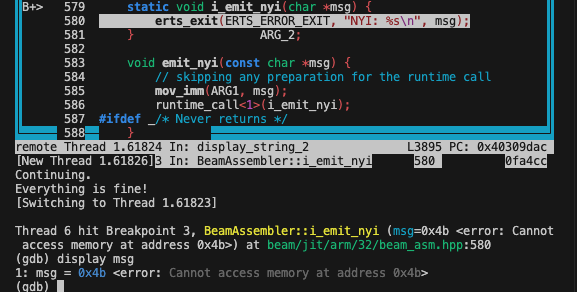

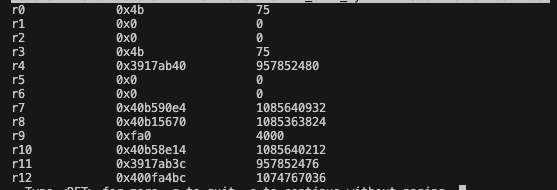

By breaking into the function we can clearly see that the msg pointer is not looking good:

This value, being the first argument, is taken from ARG1 which is r0 in ARM32

This should be a pointer to the string we want to format into the print. Instead, this is just 75. It is a clear indication that we corrupted the registers and something is off somewhere. Plus, 75 looks very much like a real value, not random garbage, which suggests we are using real data that was supposed to be somewhere else but ended up in r0 for this runtime call. Interestingly, this value also appears in r3, maybe used as a scratch register before this call.

Initially I thought this was a Heisenbug: as I attempted to insert stack alignment checks in emit_nyi, the bug would disappear. Actually, any instruction could make or break this bug...

void emit_nyi(const char *msg) {

{

a.nop(); // Adding a single NOP changes the behaviour

}

mov_imm(ARG1, msg);

runtime_call<1>(i_emit_nyi);

/* Never returns */

}Editing any emitter, or simply just changing the size of the emitted code, would misalign something and screw up the runtime call to i_emit_nyi. Even a single nop (no operation instruction) can trigger or hide this problem. I am writing this blog post on the go, so right now I still need to find where this bug is hiding. I hope it is something very stupid; I will let you know in my next blog post.

Maybe, reasoning about it, it could be something related to 8-byte alignment.

What inspires me to think about it is that, for instance, sometimes the AAPCS32 calling convention requires the stack pointer to be 8-byte aligned.

This is required in function calls, but I already verified that this is not the issue.

The fact that adding a nop changes the behaviour tells me something really odd is at work here. Somehow, the size of the code makes or breaks a runtime call, and this has to do with 4-byte shifts, as the nop operation is, like every other op, 4 bytes long.